It all started with the ending. It often does…

The thunderous cacophony of trumpets, percussion, and organ, roaring endlessly.

For what reason? Because it’s loud? Loud for loudness’ sake? Because that which is loud is recognized as worthy?

By no means!

Loudness in music is powerless without a cause to become loud.

Cause is powerless without direction, which is powerless without sincerity.

My addiction to victorious finales is deeply embedded in me. Based on my own story.

But victory is never without great tribulation – ‘unyielding resistance’ - defiant toward even your most fervent efforts.

Hence, the 1st movement’s 19-minute Adagio section followed shortly after…

My struggles. As a kid - socially inept and bullied. Today - as I write this with arthritic hands. An underlying desire to face my own impossible obstacles - often by choice, out of my dissatisfaction - and muster the ‘heroic capacity’ to emerge above the resistance as victorious. Incapable of being shaken. That is my direction. My ambition.

To imagine a better world, free of division, suffering, pain, violence, death - perhaps with Divine intervention. To remain passionate about topics I care for and individuals I love. To protect those from the struggles I currently face. To always pursue justice and truth. Striving for the prevalence of decency and beauty in all things. That is my sincerity.

Sincerity does not merely recognize an injustice - natural or manufactured. It identifies with those the injustice is placed upon. It places that injustice on its own shoulders, real or imagined. Thus, sincerity nurtures empathy, because empathy nurtures love.

Imagination is the engine to the composer’s voice, and fuels empathy. By connecting with and embracing my own physical and emotional suffering, I can imagine yours. By connecting to yours I embrace my audience. I embark on my voyage to “possess other eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them sees.” Pain is our common struggle, our common universe. Through great pains we are all connected, our scars healing differently over time.

Sincere writing, therefore, does not merely pay tribute to those afflicted by injustice. It does not merely give Moments of Silence. It connects with their affliction through empathy - summoning feelings embedded into the scars from our own pain – past or present - to imagine ourselves in their shoes. To possess ‘other eyes.’

Empathy is a two-way street. When you truly empathize with someone, you empower them with new, raw energy. That energy is often returned.

But it does not end there. Prior to leaving their universe, sincerity removes the pain from their universe and replaces it with perhaps the most humane element – hope. Our greatest struggle is our waning capability to hope for a better world, guilty by age. There is no greater power ‘under the sun’ than music that serves as a vessel toward our common decency - our reason to hope.

To listen to music is to enter the composer’s imagined universe. My source of inspiration to create comes from the power of believing that my imagined universe can positively impact the real one – having channeled my the ‘other eyes’ I hear - through the cries of my own affliction, and embedding it through music to help others overcome theirs. I fail more often than I succeed.

Failure is a form of personal affliction, often stemming from our dissatisfaction. Empathy - thus, sincerity - is impossible without personal failure.

When I succeed, I pass my empathy - ingrained in the sincerity of my writing - to someone else, and they leave that concert a changed person, hoping for a better world. They have seen through my eyes because I first saw through theirs. The return of energy is complete.

This was my emotive state upon writing my new symphony, In Adventu Finalem.

***

When I began writing this work, the tumultuous political and ethical strife across the globe resonated deep within me. Everyone has their own topics that resonate close to them. Abortions, school shootings, political correctness, institutional racism. For me, it’s political hyper-conformism – treating issues as black and white. The notion that only one way is the right way, and that way is either Democrat or Republican. Hyper-conformism leads to deep, lasting division, apparent even long after the world premiere of this work, as it seeps through like a poison into individuals, communities, media, and even presidents.

Division leads to violence, physical or verbal.

Violence leads to manufactured, unnecessary pain. Pain among individuals, families, communities, nations. Pain reverberates like a splash in a tranquil pond.

In Adventu Finalem is a protest against violence. It is a story fabricated from my own deep frustration with global affairs. It is the reconstruction of my imagined universe - in this case violently clashing with the real one – to serve as a warning. It denounces violence by providing a window into a bleak world riddled with catastrophe. Perhaps even more impacting, it is a window into a world that looks frighteningly familiar up close, one that fills us with horror upon realizing that it is our very own – that from an chilling, sobering perspective. A world looming with a subdued perpetual terror that was founded over 70 years ago amidst mankind’s decision to defy the ‘force of which the Sun draws its power’ by attempting to recreate that power for their own ambitions, what then became one of the most consequential acts in human history - unleashing the power of the atom bomb, and the ensuing nuclear age.

Surely, mankind faced more violent moments of tribulation. But there was perhaps no act more consequential toward the long-term mental well-being of humanity.

This work was, by circumstance, written and premiered during a highly unstable time between US relations with North Korea and Russia. Every decade or so the country changes, but the threats do not, as the civilians of each nation watch with awe and disgust at these power games.

To be clear, this work is not about nuclear warfare. It merely uses nuclear warfare as a vessel to describe the most blatant manifestation of the real underlying issue – violence, in turn caused by division, in turn caused by lust for one’s self-interest, lack of empathy toward others, and allowing anger to cloud one’s judgement without considering the harm it causes someone else.

Perhaps one word sums that up best - indifference. Perhaps indifference is what I am really after. Indifference toward others. Indifference toward consequences of one’s actions.

Indifference is naturally divisive, and thus breeds violence. Indifference lures our selfish desires by exclaiming ‘your problems are not mine,’ a notion that initially sounds enticing, especially with our own daily burdens. It changes our behavior to think only of ourselves as individuals, communities, or nations and tunes out everyone and everything else, regardless of circumstance, unless their purpose in some way is subservient to our own. Yes, indifference is the perfect recipe for violence.

This work protests these aforementioned traits, chiefly through nuclear warfare, in two ways:

1) It reflects on past mistakes, specifically our decision to obliterate Hiroshima and Nagasaki

2) it reflects on the cataclysmic outlook our future mistakes could cause us. Both serve as a reminder of why violence is never the answer and that we must remain united as a people- as a species - by empathizing with others and avoiding the temptations of indifference.

But it doesn’t end there! It’s not simply a work that pays tribute. Sincerity is naturally empathetic. Empathy fights our internally selfish desires to remain indifferent to the affliction of others. Acknowledgement can generate empathy, but it alone does not have the power to guarantee it. Thus, music written as a tribute does not have the power to dramatically change its listeners, but rather serves to reflect, mourn over, and acknowledge an injustice before moving on. Sometimes this is necessary. Acknowledging the importance of peace in the wake of violence can be meaningful and moving; but it often does not have the power to change people to actively reject violence. However, a constant wave of empathy - through sincerely-written music - I believe does have the power to change people. Our past shows this. Art has always been mankind’s attempt to control the forces of nature, both within and outside of us.

Only when one can truly glimpse into the real horrors of a world that was once someone else’s and could one day become their own will one’s outlook truly change.

***

By listening to the 1st movement, Perspective, the audience glimpses into the utter, incomprehensible suffering of innocent civilians killed and injured by the atom bomb, at the time the world’s deadliest weapon.

This movement realizes this in a few different ways. The most transparent example was my choice to embed the score with [unspoken] text from some of the victims who survived the a-bomb. Upon my searching for such quotes, I came across stories that were intensely petrifying, stories that bred images so graphically nightmarish that I chose to leave them out. Victims described looking around a blood-orange sky surrounded by flames and butchered corpses and accompanied by the smell of burnt or rotting innards. Those who were still alive were severely burnt and naked, aside from the trails of their own clothes melted and permanently affixed onto their skin like tattoos. Fingernails fell off their fleshy hands effortlessly, accompanied by an oozing black slime trailing down their bodies. A young schoolboy looked into the eyes of his dying friend only to realize his friend’s eye was freely dangling out of its socket. A mother, disoriented from her natural state, looked into the eyes of her frightened child, who was helplessly trapped in the crushing rubble as the fires drew closer. The child called out to her mother as the mom stumbled away in tears, unable to muster any energy to pull her out. “Nightmare” does not even begin to describe the events

The audience at the premiere was unaware of the embedded text (save the text at the end of this movement), as I felt it would have been too much to handle and may even spark division in and of themselves. It’s difficult to speak of historic decisions involving the instantaneous mass murder of civilians during a war and how those decisions reverberate in our state of affairs today without causing division, the very thing I am protesting against. They did, however, have the program notes, which offered a glimpse of the gut-wrenching nature behind the work, which was, along with my other strategies, more than sufficient to gather their interest as the movement came to its haunting close. Ideally, I would like this text to be made public, either in the program notes or projected in real time during the work’s performance.

A second strategy I used was that of sheer force of the ensemble, collectively coming together with the organ following the opening section of the Adagio. The performers brilliantly exerted such a massive wall of sound that was truly spectacular to behold in person. A raw moment of cacophonous power that inspired wonder over the prospects of the Divine. Loudness with a cause.

But not without contrast, that of the main theme’s quiet innocence heard in the previous section, reinforcing the moment of power stated above.

Nor without this moment’s foreshadowing from the 5 minutes of confused clamor in the introduction that begins the symphony.

Nor without the long-awaited, uplifting release in the middle section when the choral, reflecting a promise awaiting to be fulfilled, is revealed for the first time. That promise is later fulfilled upon the choral’s return in the symphony’s finale.

But the mental tranquility doesn’t last, as the tensions that began the symphony return here.

The sheer force of the ensemble returns one last time in this movement’s main climax, one that insolently shatters any thread of hope in a world that unwillingly embraced the worst of humanity in the blink of an eye – a world that was real for the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Kazu-chan was the daughter left behind by the disoriented mother, and this passage is the reenactment of the mother crying out in unequivocal agony, bracing each mental tremor of excruciating pain upon realizing what she had done – she left her child to die.

Yet, so easy for us to blame her? Us, who brought forth this nightmare? Us, who could never even come close to imagining the horrors of this moment? To suddenly find yourself naked, skin-torn in rubble surrounded by living hell. At some point, your survival instincts take over without compromise nor plea. Our purest instincts have always been naturally selfish.

The final way I connect the audience to the story behind the music is by having them actively participate in the work, specifically in the ending of this movement, where I employ additional methods of captivation - the somber visual imagery of candles and a darkened house, save the dim shades of deep blue surrounding the hall and stand lights of the organ twinkling from above like a supreme entity passively overlooking. The work at this point transforms into a eulogy. The organ solo bleakly states the movement’s main theme - the cold, manufactured vibrato from the flugelhorn stop, representing the aftershocks of death, destruction, and suffering carried out just moments earlier by the movement’s massive climax, representing the ‘other eyes’ of those who lost everything. The organ solo summons the ensemble - exhausted at this point - to turn to their most basic, purest, most empathetic instrument, one that is common among all peoples no matter what background – their voices. Voices that gradually arise from the ashes and reverberate throughout the hall. It represents the summoning of new life, new innocence, a hope for a better future. A plea for peace.

And so begins the switch from a fixed, static, manufactured instrument to one that is pure, raw, variable, and imperfect, one that is human. It is this collective, imperfect sound that reminds us of our common humanity. What is perfect is naturally dispassionate and unrelatable, and is therefore inhuman. And so we sing together - imperfectly, beautifully, with all our soul – a collective display of unity against what is antithetical to our common decency – indifference. It is here when the audience joins the chorus and the organ tapers away. And so remains the unified voices of the congregation, unaccompanied, passionate. Human. An expression of our relation to all peoples and a warning against bending toward selfish incentives and divisive mindsets… “in the end, I was singing alone.”

Aside from quotations from these survivors, I also use Biblical texts, specifically from the Judeo-Christian faith. My personal faith. That which makes it my universe. The creation of a story merging real events with ecclesiastic ones, such as the Apocalypse. It shows the audience a different perspective, one that may clash with their own, but one that they take with them - one that they simply cannot forget.

My bow to religion, however, does not alienate those who don’t identify as religious. Religion has always been man’s struggle with rationalizing death and suffering. Our common struggle with pain and ambition toward decency transcends religious affiliation. I use religion as a way to dramatize the work with colorful and explicit images - immediately graspable to most audiences – that embolden the message the work seeks to unveil, all while being true to my own faith. By exploiting these images, the audience enters a world outside of their own, a world that, although evokes utterly fantastic tales, relays a theme not far unfamiliar from the state of affairs in their real world. It is, crudely so, a wake-up call in the form of Divine cataclysmic interference.

Which brings us to the second form of this work’s protest - portraying a window into a new world that reveals the disturbing direction of our own. This is the purpose of the 2nd movement, Prophecy, evoking stronger musical imagery than the previous movement. Most general listeners could follow along as to when certain events are unfolding …

The simmering tension created in the beginning of this movement.

The ongoing conflict throughout the Toccata.

The slight temporary relief from a hymn-like middle section and the calming effect it produces. The ‘calm before the storm.’

The explicit unfolding of cataclysmic events upon the movement’s ferocious climax, summoning a wall of clamorous trumpets, deafening percussive blows, and sirens. The Biblical ‘Great Tribulation.’

The organic unfolding of a major key as the former bitonal landscape – AKA ‘something that doesn’t quite fit’ – finally surrenders to the lyrical imitation between the saxophones into an uplifting tonal landscape, again accompanied by the imperfect sound of human voices.

And finally, the momentous finale that portrays the Second Coming, what first came to me - the return of the chorale and fulfillment of something great. Something earth-shattering, immutable, that which cannot be undone. It must be so! An unparalleled victory – whether a Divine Entity making herself known or, perhaps more subtly, man summoning ‘heroic capacity’ to become better than her former self, overcoming the ‘unyielding resistance’ that would seemingly not curb. That which the first 50 minutes of the work led us to. Loudness justified! Loudness in music always plays a subservient role to direction. It is by no means a primary method of engaging your audience.

Although sometimes it would seem so with this work, being even louder than works that rely on loudness for loudness’ sake. I suppose one ‘ought to see far enough into a hypocrite to see even his sincerity.’

***

Now what about what I said above will general listeners actually understand upon first hearing the work? None. But the term “understand” typically suggests something involving our conscious judgement based on what we know about music, which is highly subjective based on our varied cultural backgrounds. For those who, like myself, are literate with common practice and contemporary concert music, this work is judged. It is judged because the pride of our musical literacy demands judgement. To those illiterate, this work is felt. To those literate, I ask what did they think about the piece they heard? To those illiterate, I ask what did they feel? These terms are not exclusive to one party, but they are often what each party first associates themselves with.

This is because it is intuition that captivates general listeners, but it must be relatable to them in some way, hence the need for empathy in one’s writing.

My grandfather, who is unfamiliar with classical and contemporary styles, attended this premiere. He exclaimed to me, “I enjoyed what he heard but did not understand it.” What fascinates me was he stated this as if he was missing something from what he could had otherwise attained with stylistic literacy. But why must a work be understood if it is enjoyed? The best composers write music that relates to their audience without compromising their own styles. That is, music that the literate understand and the illiterate enjoy without the need to understand, but with the curiosity to better understand. We all have a underlying curiosity to learn more about that which we do not fully grasp; such curiosity is another device I rely on in my own writing.

What listeners feel in music is connected to what they experience in their own lives, especially works that strongly attribute to one of the five senses. Some attribute music with colors. Others with images, objects, or dramatic action - a concept reinforced by films, theater, music videos, and video games. Others are reminded of personal experiences - from traumatic to triumphant - and the emotive state attached to that experience, a concept familiar to most through musical lyrics. This means that expression in music does not discriminate toward a specific style of writing because, in and of itself, music is incapable of expressing anything at all! Regardless of whether the work is tonal, polytonal, or atonal, the pitches themselves don’t mean anything. It’s the meaning that the composer, and ultimately the listener, attaches underneath the pitches.

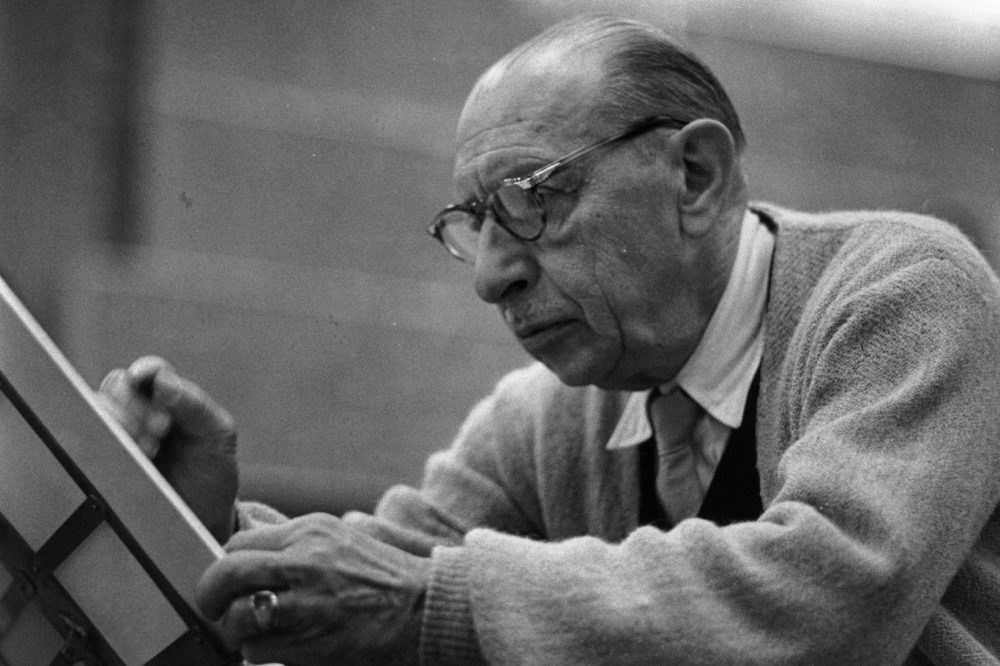

Stravinsky’s understood this via his quote. I highlighted the portion of which I find particularly interesting:

“For I consider that music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all, whether a feeling … attitude …, mood, a phenomenon of nature, etc. Expression has never been an inherent property of music. That is by no means the purpose of its existence. If … music appears to express something, this is only an illusion and not a reality. It is simply an additional attribute which, by tacit …, we have lent it, thrust upon it, as a label, a convention – … an aspect which, unconsciously or by … habit, we have come to confuse with its essential being.”

I interpret this as follows: music in and of itself is powerless to express something. However, humanity has often attributed music with expressive topics, rhythms, and circumstances to the point where we have collectively created the illusion that music itself is expressive when it is really the meaning we attach with it that is expressive. This meaning is subjective based on the physical or emotional experiences of each listener, and will create a different mental attachment to the music based off of the meaning that music reminds that person of in his or her own life. Music, rather, becomes a gateway toward - but not the means to - discovering something about who we are as individuals and as a society, perhaps the most genuine form of expression. It becomes a way of unraveling something, whether known or unknown at the time, about our very selves.

Just because it is imagined doesn’t make the process of expressing ourselves through music meaningless. It is our imaginations – our illusion - that gives something as abstract as music its power of expression. Music, then, serves is a vehicle for unlocking, channeling, and manifesting our own forms of expression. And the power of music as an expressive tool becomes even greater when it becomes collectively felt and utilized by large masses.

***

To submit oneself to the universe of your audience does not mean a composer compromises his or her own personal style. It does mean, however, that the composer must compromise his or her own selfish tendencies to become indifferent. Indifferent to his or her audience, culture, or environment in favor of petty self-interests. Indifference is the antithesis to empathy. Empathy is the window to the ‘other eyes’ of your audience. Composing is, therefore, not simply a profession - it is a lifestyle choice.

When composing music absent of empathy you only write music that is judged rather than felt, thus alienating your audience to only those who are musically literate. When the self-interest of exploring ‘strange lands’ exceeds the desire to write sincerely, you write music that lacks meaning outside theoretical purposes. Rather, it is best to balance both traits - empathy and originality. In fact, both feed on each other.

Like empathy, indifference is a two way street. Indifference toward your audience will always be returned. Indifference is the antithesis to engagement, and engagement is every composer’s purpose in music.

Composing for approval, ironically, is a form of indifference, as it ultimately points to the composer’s own self-interests of gaining acceptance. Whether it’s your audience or your collegiate peers, you must write for yourself - sincerely.

Empathy can also exist by composing works depicting non-expressive entities that appeal to the senses, such as the smell of earth after rain. By itself, no emotion is attached to such an idea; however, being that it appeals to the sense of smell, as well as portraying a stunningly evocative image, composers can channel the human senses to reflect differing emotive states based on this idea.

***

Concerning the medium for which I wrote this work for, In Adventu Finalem exists to object to any form of insincere or ‘trendy’ writing. It was written not because I feel the medium wants this work, but because I feel it needs this work. The world needs this work – unbeknownst to them, perhaps forever. People need to hear it not for the sake of the work itself, but for the message it encompasses. This is not about self-aggrandizement, but rather serves as a challenge to the current trends and schools of thought that wind ensemble music seems to currently cultivate, a direction toward stylistic singularity, specifically toward tonal music with strong populist roots. Tonal and popular music in and of themselves are not the issue. Rather, it’s the erroneous belief that these styles, alongside loudness, are the means to achieving audience engagement. They are not! By itself – music expresses nothing. And it is often insincerely written when writing in these forms - not because of talent or lack of, but because they are written in hopes of gaining approval or conforming to a stylistic ideology that remains static over time.

What a composer attaches to the pitches – whether a story, image, lyric, or other extra-musical context – and how the audience relates to that attachment through their own experience and the emotional journey the pitches take them on ultimately determines how they feel about the music they listen to. That journey does not require theoretical understanding nor familiarity pertaining to a musical style – in other words, the musical style used in one’s composing plays very little role in the audiences’ feelings on what they experience temporally. That which is felt need not be understood. Music is felt by attaching expression to it, although that expression does not originate within music itself.

This belief does not discriminate against tonality or popular music. I myself am more often a tonalist than not, and I know many tonal composers who write sincerely. I also love the popular classics as well as EDM music. Heck, I made an EDM demo for an electronic music class I took in college. And if you thought I wasn’t going to share that demo with you, you thought wrong! CLICK HERE!

Rather, this belief lifts any discrimination against musical styles that fall outside the subtly yet narrowly-defined aesthetic norms that currently prosper. Carrying out this belief will ultimately contribute toward the diversity of musical styles that will ultimately breed a more pluralistic tone, one that I believe will greatly benefit the medium.

I hope the message of this work will be heard and felt. I hope my imagined universe this work portrays will positively impact this one.

I cannot thank Jerry Junkin and the Dallas Winds enough for helping me bring this symphony alive. It was such a blast [literally] working with them! Maestro Junkin was with me since the conception of this work, aware of the emotive boundaries I was intending to cross. I am so grateful for his continuing support.

You may listen to it in its entirety HERE. A VIDEO of the premiere is also available.